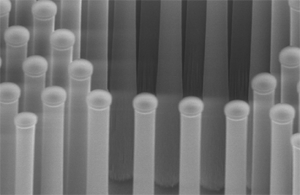

A scanning electron microscope image of tiny silicon pillars, used to absorb light. When dotted with the new catalyst and exposed to sunlight, these pillars efficiently generate hydrogen gas from the hydrogen ions liberated by splitting water. Each pillar is approximately two micrometers in diameter. (Image courtesy of Christian D. Damsgaard, Thomas Pedersen and Ole Hansen, Technical University of Denmark.)

Menlo Park, Calif.—Scientists# have engineered a cheap, abundant alternative to the expensive platinum catalyst and coupled it with a light-absorbing electrode to make hydrogen fuel from sunlight and water.

The discovery is an important development in the worldwide effort to mimic the way plants make fuel from sunlight, a key step in creating a green energy economy. It was reported last week in Nature Materials by theorist Jens Nørskov of the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University and a team of colleagues led by Ib Chorkendorff and Søren Dahl at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

Hydrogen is an energy dense and clean fuel, which upon combustion releases only water. Today, most hydrogen is produced from natural gas which results in large CO2-emissions. An alternative, clean method is to make hydrogen fuel from sunlight and water. The process is called photo-electrochemical, or PEC, water splitting. When sun hits the PEC cell, the solar energy is absorbed and used for splitting water molecules into its components, hydrogen and oxygen.

Progress has so far been limited in part by a lack of cheap catalysts that can speed up the generation of hydrogen and oxygen. A vital part of the American-Danish effort was combining theory and advanced computation with synthesis and testing to accelerate the process of identifying new catalysts. This is a new development in a field that has historically relied on trial and error. If we can find new ways of rationally designing catalysts, we can speed up the development of new catalytic materials enormously, Nørskov said.

The team first tackled the hydrogen half of the problem. The DTU researchers created a device to harvest the energy from part of the solar spectrum and used it to power the conversion of single hydrogen ions into hydrogen gas. However, the process requires a catalyst to facilitate the reaction. Platinum is already known as an efficient catalyst, but platinum is too rare and too expensive for widespread use. So the collaborators turned to nature for inspiration.

They investigated hydrogen producing enzymes—natural catalysts—from certain organisms, using a theoretical approach Nørskov’s group has been developing to describe catalyst behavior. 'We did the calculations,' Nørskov explained, 'and found out why these enzymes work as well as they do.' These studies led them to related compounds, which eventually took them to molybdenum sulfide. 'Molybdenum is an inexpensive solution' for catalyzing hydrogen production, Chorkendorff said.

The team also optimized parts of the device, introducing a 'chemical solar cell' designed to capture as much solar energy as possible. The experimental researchers at DTU designed light absorbers that consist of silicon arranged in closely packed pillars, and dotted the pillars with tiny clusters of the molybdenum sulfide. When they exposed the pillars to light, hydrogen gas bubbled up—as quickly as if they'd used costly platinum.